Starvation and Bad Treatment

When the Civil War began in April 1861, the United States had only a small standing army. Over the next year, volunteer regiments were recruited from all the Northern states. One such regiment was the 103rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, which was established in Kittanning, Pennsylvania, northeast of Pittsburgh, and enlisted men from the midwestern section of the state (Dickey 1910). Five of my relatives were among the men who volunteered for this regiment. These included my four-times great-grandfather Reese Thompson, who was nearly 50 years old but told the army he was 43, his 14-year-old son Milton, and his nephew and namesake Reese Shay.

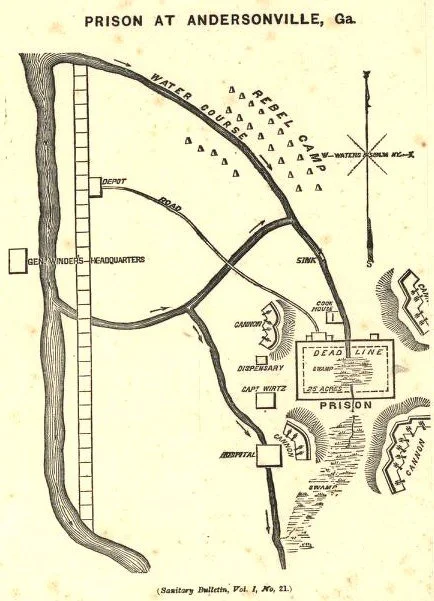

United States Sanitary Commission. 1864. Prison at Andersonville, Georgia. New York: Waters & Son.

Reese Thompson’s older son John, my three-times great-grandfather, also enlisted, but in a cavalry regiment, leaving behind a wife and two small children. His wife Peninah’s brothers, John and William Wion, also enlisted in the 103rd Infantry.

The motivation for these enlistments was probably economic. In August 1861, Congress increased military pay, and soldiers also received a bounty of $100—a substantial amount at that time—after serving their enlistment (Marvel 2005). The prospect of regular pay and a large bonus, together with the opportunity to serve their country, was undoubtedly appealing to men working as coal miners and farm laborers. What they couldn’t know is that they were enlisting in a regiment that would see one of the worst outcomes of the war, resulting in the deaths of more than 400 of the approximately 1,000 men in the regiment (Dickey 1910). [1]

From its initial organization in September 1861 until February 1862, the 103rd Pennsylvania Infantry didn’t leave its home state. This time was spent bringing the regiment up to strength and teaching farmers and coal miners how to be soldiers. In February 1862, the soldiers traveled by train to Washington, DC, to begin their active duty as part of the Army of the Potomac. They spent the next six months or so marching around Virginia, where they engaged in frequent skirmishes and battles during the Peninsula Campaign and participated in the Union’s unsuccessful effort to capture the Confederate capitol at Richmond. In December 1862, the regiment was sent by steamer to winter at New Bern, North Carolina, remaining there until May 1863, when they were sent to man the garrison at Plymouth, North Carolina, on the Roanoke River (Dickey 1910).

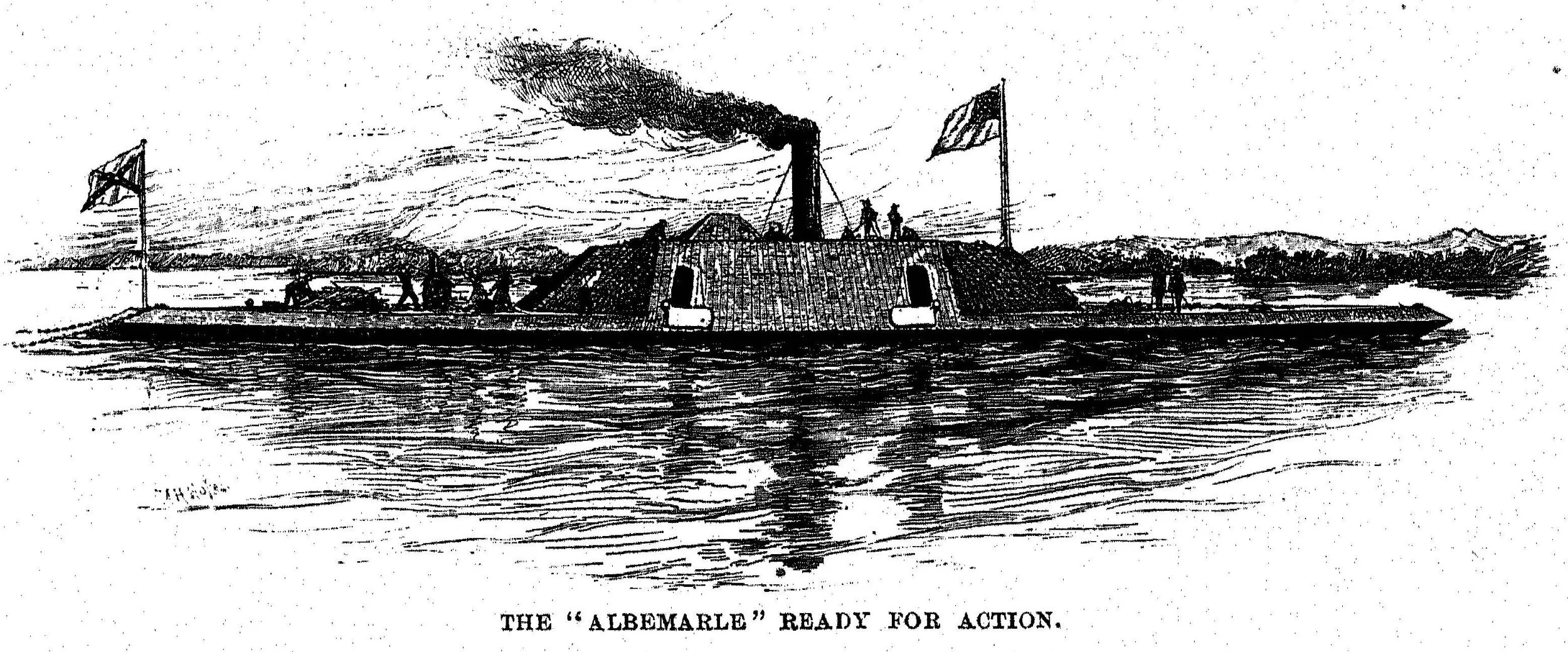

The 103rd remained at Plymouth for nearly a year and initially found garrison duty much less exciting but a good deal safer than their earlier fighting in Virginia. By the spring of 1864, many veterans of the regiment had re-enlisted and were looking forward to a furlough at home after being away for two years. On April 17, however, the Plymouth garrison was besieged by a sizable Confederate force, outnumbering the Union soldiers five to one. The Confederates also quickly gained control of the Roanoke River using the iron-clad vessel Abermarle. The 103rd defended the garrison for several days but ultimately surrendered to the Confederacy on April 20, 1864 (Dickey 1910).

“The '“Ablemarle” Ready for Action.” Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, Eds. New York: The Century Co., 1884, vol. 4, p. 633.

Among my relatives in the 103rd Infantry, Reese Shay was the most fortunate. He was a member of Company C, which had been stationed on detached duty at Roanoke Island, and thus avoided capture. He served out the remainder of the war unscathed. The four Thompson and Wion men, on the other hand, along with the bulk of the enlisted men from the 103rd, were marched under guard to Tarboro, North Carolina, and then sent in freight cars to the Confederate military prison in Andersonville, Georgia (Dickey 1910).

The issue of how to incarcerate large numbers of prisoners of war was not something Americans had dealt with before the Civil War. In previous conflicts, soldiers from the opposing forces were usually exchanged relatively quickly, sometimes immediately after a battle. When the Civil War began, however, the Union was reluctant to exchange prisoners with the Confederacy because its leaders believed that doing so implied recognition of the Confederacy as a legitimate nation, rather than an internal rebellion. Some exchanges did happen, negotiated by individual military commanders, but no formal agreement was made until July 1862, when the government yielded to public pressure and agreed to the Dix-Hill Cartel, which established principles for prisoner exchanges. The cartel broke down in 1863 because the Confederacy insisted that Black soldiers were to be treated as escaped slaves and refused to exchange them, a position that was unacceptable to the Union (Pickenpaugh 2013).

This decision forced both the Union and the Confederacy to build large military camps to house prisoners of war. Conditions in these prisons were not good on both sides of the war. Overcrowding, epidemics, and food shortages were common occurrences. The worst of the Union prisons saw death rates of 15-25%, but in general, the Union was better positioned to provide the resources needed to manage its prison camps. The Confederacy, with little industrial capacity and massive financial woes, was utterly unable to do so (Pickenpaugh 2013).

Camp Sumter in Andersonville, Georgia, where the 103rd Pennsylvania Infantry soldiers were sent, was the most notorious of the Confederate prison camps. [2] Over the 14 months of its existence, Andersonville housed 45,000 Union prisoners, of whom 13,000 died. The commander of the prison camp, Captain Henry Wirz, was executed for war crimes following the Civil War, but many historians see him as a scapegoat, taking the blame for an untenable situation caused by appalling mismanagement at all levels (Futch 1999; Pickenpaugh 2013).

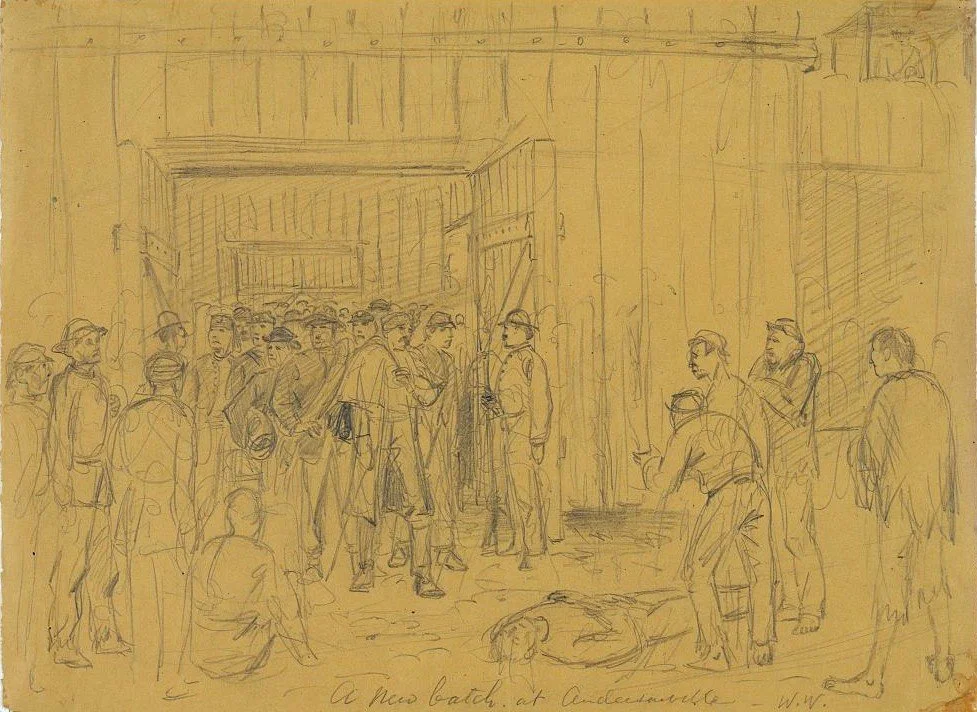

William Waud. 1864. A New Batch at Andersonville. Andersonville, Georgia.

Established in February 1864, Andersonville was simply a stretch of open land with a wooden stockade around it. There were no barracks or tents for the prisoners. What shade was to be had came from blankets attached to scavenged poles. A creek ran through the camp but was terribly contaminated, leading prisoners to dig their own wells. The food provided to prisoners consisted of rice or cornmeal with small amounts of bacon, and there were often food shortages. Many prisoners developed scurvy from the lack of fruit and vegetables. Prisoners who had some money or items to barter could occasionally get vegetables, soap, or other necessities, but they were also at risk of robbery, usually from other Union prisoners. The Confederate guards, overworked and underfed, kept prisoners from escaping but did little to maintain order in the camp (Futch 1999; Pickenpaugh 2013).

Reese Thompson was one of the many men who did not survive Andersonville. The 103rd Infantry arrived there in early May 1864, part of a massive influx of prisoners that peaked at nearly 30,000 in August 1864. Conditions that summer were brutal. With little shade, the men suffered from heat stroke and dehydration. The camp hospital could not hold all of the soldiers who came each day to be treated. Many, including Reese, died of diseases such as dysentery and are buried in the national cemetery at Andersonville (Futch 1999; Pickenpaugh 2013).

Following Sherman’s capture of Atlanta, Georgia, in September 1864, the Confederate government became concerned that Union troops would liberate the prisoners at Andersonville. Many prisoners were sent to other camps, primarily Camp Lawton in Millen, Georgia, and the Florence Stockade in Florence, South Carolina. My three-times great-uncles John and William Wion were among those sent to Florence.

At least initially, the conditions at Florence Stockade were no better than at Andersonville. There was no shelter for the prisoners, many of whom lacked even blankets, and food shortages continued to be a major problem (Pickenpaugh 2013). Supplies received from the U.S. Sanitary Commission in October 1864 helped somewhat but arrived to late to help William Wion, who died at Florence in November 1864. According to one of his fellow soldiers, “The cause of his death was starvation and bad treatment.” Soon after, his brother John was paroled and made his way to Camp Parole near Annapolis, Maryland.

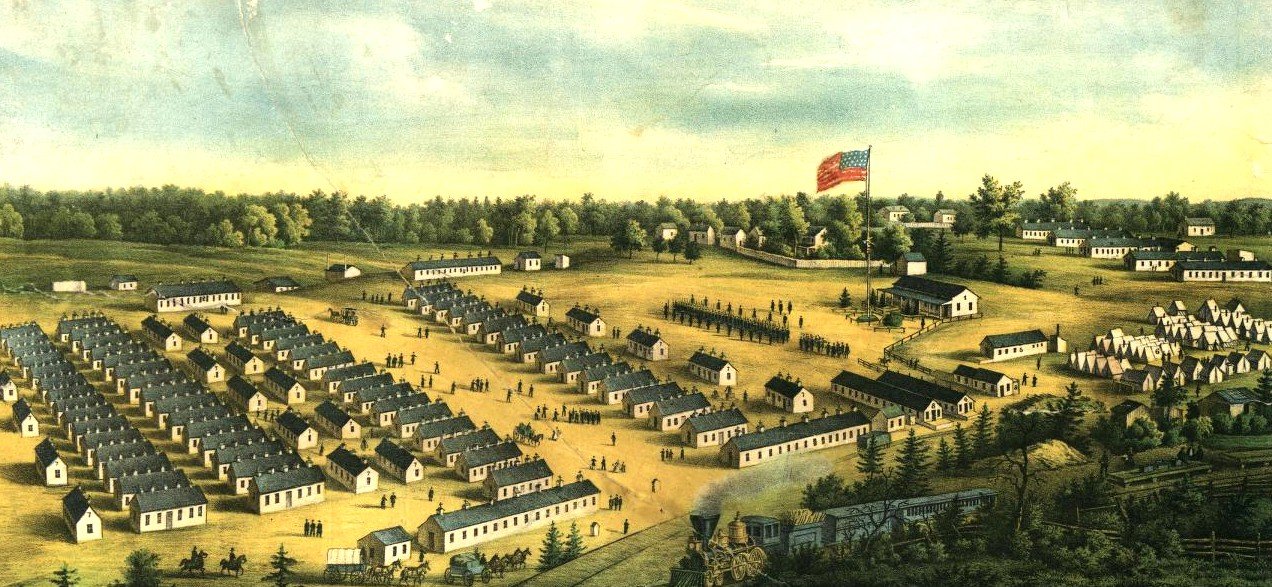

“Parole Camp, Annapolis, Maryland.” Baltimore: E. Sachse & Co, 1864.

Paroled prisoners of war were released after taking an oath not to engage in military action until they were officially exchanged. In previous wars, paroled prisoners had simply gone home, but the Union government was unwilling to release soldiers who still had time left in their enlistments. Instead, they built several military camps in which to house paroled soldiers, of which Maryland’s Camp Parole was the largest. With few prisoner exchanges happening, these camps ended up holding paroled soldiers for extended periods of time. Conflicts developed over whether paroled soldiers could legitimately be required to perform guard or clean-up duties, but without the labor of those living in the camps, they quickly became dirty and lawless. Desertion was a particular problem, as many paroled soldiers saw no reason why they should sit in a camp when they could be at home with their families (Pickenpaugh 2013). For John Wion, however, these concerns were irrelevant. He died of scorbutic bronchitis, a complication of scurvy, at the hospital at Camp Parole in December 1864.

The only survivor of the four Wion and Thompson men captured in April 1864 was young Milton Thompson. He remained at Andersonville until March 1865, when he was sent to Camp Fisk, a parole camp near Vicksburg, Mississippi. The Union and Confederacy in February 1865 agreed to a general exchange of prisoners, and Camp Fisk was a key site for that effort. It was unusual in that it held both Union and Confederate prisoners, on opposite sides of the camp. The Union took responsibility for supplying the needs of all the prisoners, and most were sent home quickly, particularly after Lee’s surrender on April 9 (Pickenpaugh 2013). Milton was released from Camp Fisk on April 21, 1865, still only 18 years old, and presumably sailed up the Mississippi River on a steamboat. He was fortunate that he left Vicksburg when he did. On April 24, the last group of soldiers departed aboard the heavily overloaded steamer Sultana, which exploded and sank near Memphis, Tennessee, killing most of the passengers (Pickenpaugh 2013).

“The Last Exchange. Camp Fisk, Four Mile Bridge (Vicksburg), April 1865.” The Photographic History of the Civil War in Ten Volumes. Francis Trevelyan Miller, Ed. New York: Review of Reviews Co., 1911, vol. 1, p. 108.

A sad footnote to this already sad story is that my three-times great-grandfather John Thompson also died at Andersonville. He was captured at Bolivar, West Virginia, in July 1864 and sent to Andersonville, where he died in October 1864. In the six-month period from July to December 1864, my three-times great-grandmother Peninah Wion Thompson—then only 20 years old—lost her husband, two brothers—one of them (William Wion) her twin—and her father-in-law. She received a widow’s pension from the U.S. government in 1866 and raised her children alone before dying at the age of 48. When people talk about the sacrifices we make for liberty and our country, she’s the person I usually think of.

[1] The overall Union casualty rate during the Civil War was about 18%.

[2] Camp Sumter was the official name of the prison camp, but it is often called Andersonville Military Prison or simply Andersonville.

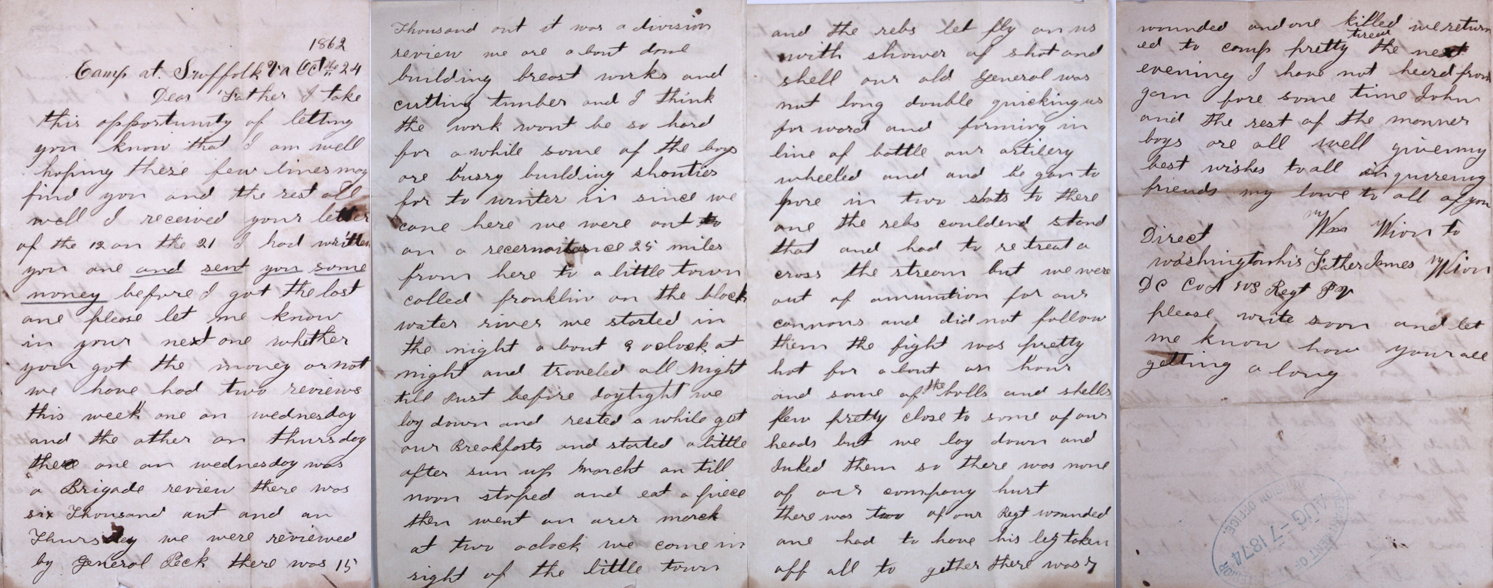

Letter from William Wion to his father James. 24 October 1862. Suffolk, Virginia. William Wion Civil War pension file. 1880-85. Washington, DC: National Archives. Photo by author.

Works Cited

Dickey, Luther S. 1910. History of the 103d Regiment Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Infantry, 1861-1865. Chicago: Western Newspaper Union.

Futch, Ovid L. 1999. History of Andersonville Prison. Revised Ed. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Marvel, William. 2010. “A Poor Man’s Fight.” The Civil War’s Common Soldier. Fort Washington, PA: Eastern National.

Pickenpaugh, Roger. 2013. Captives in Blue: The Civil War Prisons of the Confederacy. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press.