Airship Dreams

It seems like many of my ideas for blog posts come from finding mysterious family photos that, once researched, yield insight into things I knew very little about. Today’s post originated with a photo of my grandmother’s family standing in front of a large pile of debris. I had no idea what to make of this image, but I was certainly curious about it.

My great-grandmother Henrietta Switzer Barnhart (left) and my grandmother Dorothy Barnhart (center facing camera) with other relatives in front of the wreckage of the USS Shenandoah, Neiswonger farm, Noble County, Ohio, circa September 4,1925. Barnhart family photo. Photographer unknown.

My father, whose research has included aviation history, was able to set me straight. The family was standing in front of the wreckage of the naval airship U.S.S. Shenandoah, which crashed in eastern Ohio on September 3, 1925. The wreckage was scattered across twelve miles with the largest piece on the Neiswonger farm in Noble County, OH, about a hundred miles from where my grandmother lived in Columbus, and her family—along with many others—must have gone to see it.

The 1920s were the age of airships. After the use of Zeppelins by Germany during World War I, other nations came to see airships, specifically rigid airships, [1] as the future of aviation and essential additions to their military capacity. The United States was no exception. The U.S. Navy set out to acquire several airships, including building the ZR-1, which became the Shenandoah, based on the design of a captured Zeppelin, and purchasing the ZR-2 from England. When the ZR-2 crashed in 1921 before even attempting the trans-Atlantic crossing from England to the U.S., the Shenandoah became the focus and ultimately the flagship of the Navy’s rigid airship program (Copas 2017).

Parts for the Shenandoah were manufactured at the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia and then assembled at the Naval Air Station in Lakehurst, NJ, where an enormous hanger had been built to house the Shenandoah and the ill-fated ZR2 (Copas 2017; NASM 2023). Construction of the airship took several years and cost millions of dollars, with additional millions spent on constructing the Lakehurst hanger and its mooring tower. Lifting gas for the airship was also an added cost. The Shenandoah was the first airship to use helium, as opposed to the highly flammable hydrogen used by earlier airships (NASM 2023). At the time, the U.S. was the only nation with the capacity to extract helium from natural gas, and filling the Shenandoah’s 2.1 million cubic foot gasbag took nearly all the helium available at that time (Litchfield 1927).

The Shenandoah was finally launched in October 1923, with a test flight that took the chief of the bureau of naval aeronautics to an airshow in St. Louis, a trip he called “delightful” (Los Angeles, CA, Times, 4 Oct 1923, page 3).

The airship was christened on October 10, 1923, by the Secretary of the Navy, who then took his wife and son with him on a flight along with the families of several of the airship’s officers (NASM 2023).

Christening ceremonies for USS Shenandoah (ZR-1), held inside the airship hangar at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, New Jersey, 10 October 1923. Collection of the Society of Sponsors of the United States Navy. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph.

Over the next few months, the Shenandoah made flights to its namesake Shenandoah Valley in Virginia and, after several weather delays, to New York and Massachusetts.

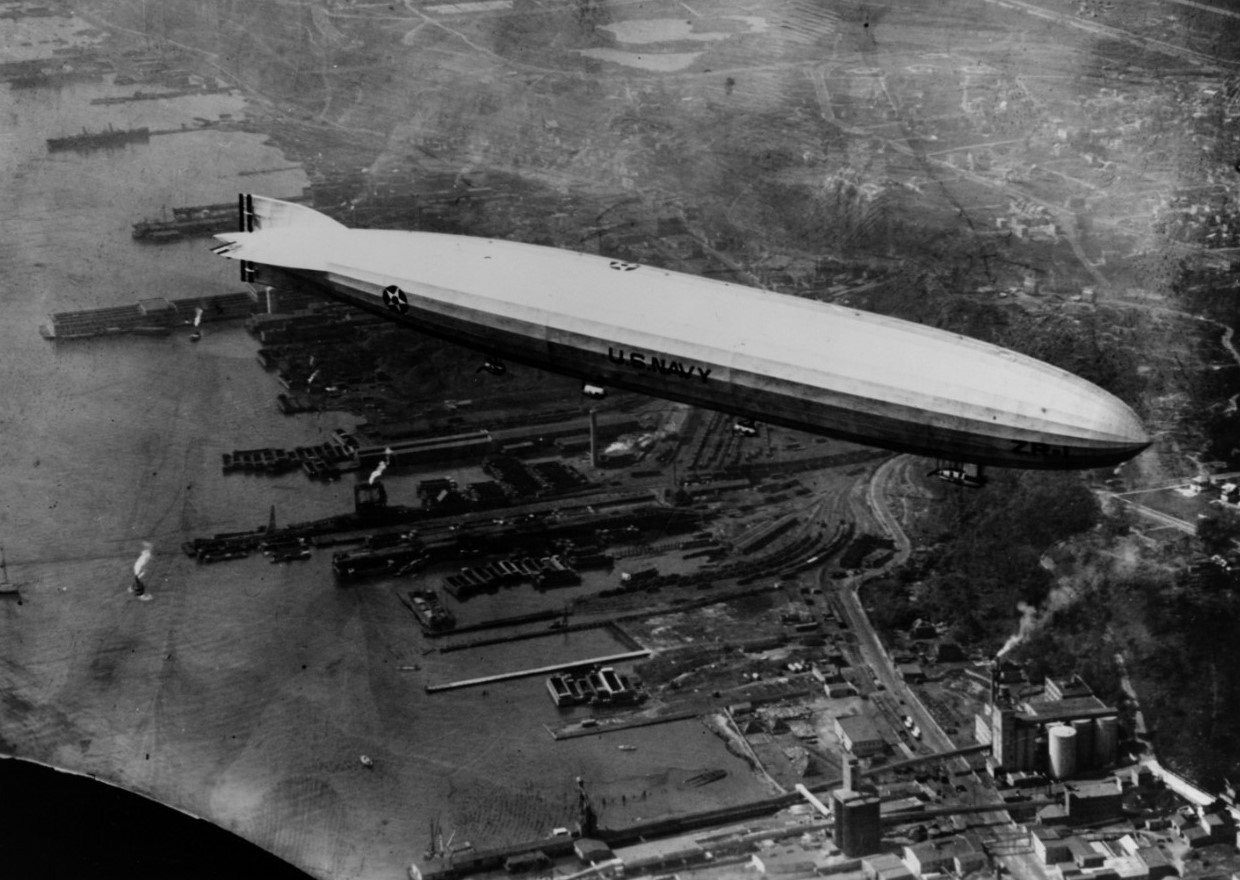

USS Shenandoah (ZR-1) flying in the vicinity of New York City, circa 1923. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph.

These flights received enormous public and media attention, as can be seen in the following headlines:

“Big Dirigible Sails Far Over Football Field: Gets Great Greeting in Valley and Beautiful Sight Draws Admiring Cries Here.” Lynchburg, VA, News and Advance, 28 Oct 1923, page 1. [2]

“Missed Big Airship: Bell Telephone Operators Swamped with Calls During the Time of its Visit,” West Chester, PA, Daily Local News, 27 Oct 1923, page 1.

“Giant Airship Shenandoah Flies Over City: Thousands Drop Work to Get a Peep at the Big Silver Bag,” Fall River, MA, Globe, 20 Nov 1923, page 1.

The nation, it seemed, had gone airship crazy, and the federal government hoped to capitalize on that enthusiasm, with President Calvin Coolidge authorizing plans for an arial survey of the North Pole in summer 1924. These plans also received considerable media attention, with articles on polar exploration by airship in Popular Science Monthly and Scientific American (Green 1924; Member of the Board 1924). The expedition was not to be, however. In January 1924, the Shenandoah began a seven-day mooring test on the mast at its Lakehurst base. Four days into the test, a storm tore the airship loose from the mast, breaking off the nose cap and sending the airship flying over Staten Island, NY, before the crew was able to regain control and return to the hanger (Walker 1924). Shortly after, the North Pole expedition was cancelled.

This minor disaster seems to have quelled the Navy’s most ambitious plans, and the Shenandoah rather quickly disappeared from the news as it underwent significant repairs, with only occasional rumors or announcements of planned flights, most of which never took place (Scientific American Staff 1924b). By the summer of 1924, however, the airship had been fully repaired and made a number of flights, including a demonstration of its ability to be successfully moored to a ship at sea (Copas 2017).

In October 1924, the Shenandoah undertook its most ambitious trip yet, a 19-day, 9,000 mile cross-country tour. The airship made stops at Ft. Worth, TX, San Diego, CA, and Tacoma, WA—these being among the few places that had mooring towers suitable for such a large airship (Copas 2017; NASM 2023). [3]

The USS Shenandoah moored at Ft. Worth, TX, circa October 9, 1924. Barnhart family photo. Photographer unknown.

A writer for National Geographic was among the passengers on this trip and gave a detailed report on his experiences in a January 1925 article, concluding that “a new era of transportation is coming nearer, in which the airship will have place as a conveyance of peace as well as an instrument of war” (Wood 1925).

In 1925, the Shenandoah made occasional flights, some related to military exercises but most intended to build public support for the naval airship program, which had been expanded in late 1924 with the acquisition of the ZR3, later christened the USS Los Angeles, from Germany. Opportunities to use the Shenandoah were limited, however, because the U.S. had only enough helium to fly one airship at a time and had to transfer the gas from one to the other as needed (Copas 2017).

On September 2, 1925, the Shenandoah departed on a 3,000 mile publicity tour of 11 states in the Midwest. Only one day into the trip, the Shenandoah was caught in a severe thunderstorm and ripped apart by turbulence. The control car suspended below the gasbag fell to the ground, killing the airship’s commander and six crew members. Seven other crew members died when the gasbag broke apart, but the remaining twenty-nine crew members were able to ride surviving portions of the airship safely to the ground (Walker 1925; Copas 2017; Vickers 2018; NASM 2023).

The places where the various portions of the airship landed immediately became tourist attractions, as can be seen in my family’s photos. There was also extensive looting of the crash sites, and one enterprising farmer charged people $1 per car to see the wreckage that had landed on his property. In an effort to gain control of the situation before vital evidence was lost, the Department of Justice sent agents to secure the crash sites and retrieve looted items such as the airship’s logs through door-to-door searches (Copas 2017; Vickers 2018).

Wreckage of the USS Shenandoah, Neiswonger farm, Noble County, Ohio, circa September 4,1925. Barnhart family photo. Photographer unknown.

A months-long formal inquiry into the disaster raised considerable controversy. The airship commander’s widow alleged that he had resisted undertaking the trip because of the potential for bad weather and had been overruled by his superiors. An airship expert testified that crucial safety valves had been removed to reduce the loss of expensive helium. Still other witnesses argued that human error was to blame for the crash and that the storm the airship encountered could have been avoided based on meteorological information. In the end, however, the inquiry board unanimously ruled that no one was at fault, calling the wreck “part of the price that must be paid in the development of any new and hazardous art” (Cleveland, OH, Plain Dealer, 2 Jan 1926, page 1).

This rather callous dismissal of the loss of human life contrasts sharply with the idyllic picture of airship travel presented in the media of the time. Whether envisioning comfortable passenger travel or trans-Atlantic mail delivery, airships were depicted as the utopian future of aviation (Klemin 1925; Wood 1925). But this depiction ignored the reality that these airships were dangerously fragile. The Cincinnati, OH, Enquirer, for example, reporting on the crash of the Shenandoah, listed eight other airship disasters that occurred between 1919 and 1923, resulting in the loss of 140 lives (4 Sept 1923, page 2).

Nonetheless, American leaders continued to promote the airship. After the Shenandoah crashed, Scientific American editors wrote, “It would be a fatal error to abandon lighter-than-air navigation because of the Shenandoah tragedy… the airship has an assured future for transatlantic and other transoceanic travel” (Scientific American Staff 1925). The president of the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company weighed in, too, arguing for “a determination on the part of this government not to lag behind, or to accept the Shenandoah disaster as anything other than a challenge to American engineering and operating genius” (Litchfield 1927). [4]

These voices were far louder than those who argued against airships as dangerous and much too expensive to maintain. When the Empire State Building opened in 1931, it included a dirigible mast, envisioning future passenger travel by airship. The naval airship program continued, as well, with construction of the USS Akron and USS Macon in the early 1930s (Moffett 1930). Both of these airships crashed during storms after less than two years of service, but it was only after the Hindenburg disaster in 1937 that the U.S. finally gave up its airship dreams (Copas 2017). [5]

Riddiford, Charles E. 1925. “Pictorial Diagram of the Ship That Made the Historic Flight.” National Geographic Magazine 47 (1): 8.

[1] Rigid airships, unlike blimps or hot air balloons, have a structure inside their gasbags that maintains its shape even when the lighter-than-air lifting gas is vented.

[2] For those interested, the Virginia Military Institute was playing North Carolina State University.

[3] Landing an airship, rather than mooring it, is a complicated process that requires a large, well-trained ground crew and may also require venting expensive helium. In any case, the Lakehurst hanger was the only one large enough to hold the Shenandoah (NASM 2023). On a side note, the reason a mooring mast was built in Ft. Worth is because that was where the principal helium extraction facilities were located (Wood 1924).

[4] Of course, he may have had ulterior motives since Goodyear was the sole American producer of the rubberized fabric skin used on airships.

[5] If the story of the USS Shenandoah has piqued your interest as it did mine, the National Air and Space Museum has an interactive online exhibit commemorating the 100th anniversary of the airship’s launch.

Works Cited

Copas, Jerry. 2017. The Wreck of the Naval Airship USS Shenandoah. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

Green, Fitzhugh. March 1924. “Perils of Polar Flight.” Popular Science Monthly 31-33.

Klemin, Alexander. 1925. “Can Huge Dirigibles Supplant Our Ocean Liners?” Scientific American 132 (2): 18-21.

Litchfield, P.W. 1927. “Lighter-Than-Air Craft.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 131: 79-85.

Moffett, William A. 2 November 1930. “Construction of Rigid Airships to Continue.” Cincinnati Enquirer Sunday Magazine, page 3.

Member of the Board on Arctic Exploration. 1924. “Arctic Exploration by Aircraft.” Scientific American 130 (3): 152-3.

National Air and Space Museum [NASM}. 2023. The United States Navy’s First Rigid Airship.

Scientific American Staff. 1925. “Our Point of View.” Scientific American 133 (5): 300.

Vickers, Jim. September 2018. “The Crash of the USS Shenandoah.” Ohio Magazine.

Walker, J. Bernard. 1924. “A Wild Night on the ‘Shenandoah’.” Scientific American 130 (3): 158.

Walker, J. Bernard. 1925. “The Tragedy of the ‘Shenandoah.” Scientific American 133 (5): 301.

Wood, Junius B. 1925. "Seeing America from the' Shenandoah'." National Geographic Magazine 47 (1): 1-47.