Heresy, Whaling, and Coffee

Any of my friends will tell you that I love Starbucks coffee. I’m a coffee fanatic, in general, but I’ve always particularly enjoyed Starbucks. While in Seattle one time, I even visited the original location. So when I discovered that I am descended from a Starbuck, I was delighted and intrigued.

Edward Starbuck, my 11-times great-grandfather, was born in England in 1604 and came to North America with his wife and children in 1642. They settled in Dover on the Piscataqua River, in what is now New Hampshire but at the time was part of the land granted by King James I of England to the Plymouth Company. Initially, Edward prospered in Dover, receiving several grants of land, becoming an elder of the church, and being elected as a representative to the general court (Scales 1900; 1923).

In 1648, however, Edward ran afoul of the local religious authorities. On October 3, he was admonished and fined for “disturbing the peace of the church.” On October 18, a grand jury indicted him “for denyeinge to joyne with the churche in the ordinance of baptisme” (Scales 1900). In other words, he was an Anabaptist and argued that adults should be baptized into the church rather than infants. He was ordered to go to Boston to be tried by the Court of Assistants (Scales 1900; 1923). I’ve not been able to discover if he was actually tried, and if so, what sentence he received. [1] Based on Massachusetts law, he should have been banished from the colony (Miller 2008), but he continued to live in Dover until 1659, when he and his family moved to Nantucket (Scales 1900; 1923).

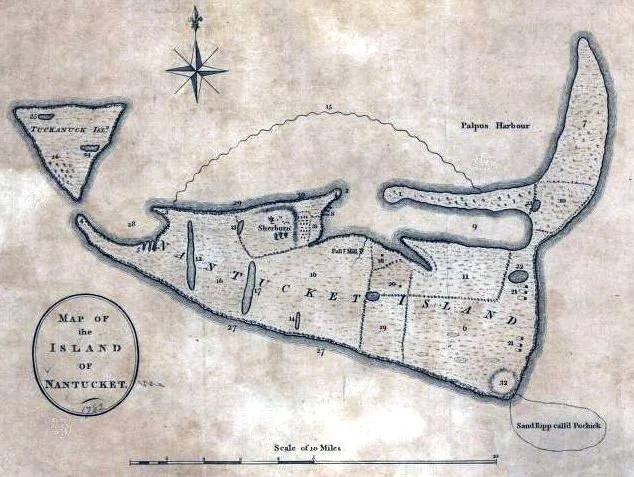

St. John De Crèvecoeur, J. Hector. 1782. Map of the island of Nantucket. London. Image from the Library of Congress.

It's not surprising to find religious intolerance in colonial New England. Massachusetts Bay Colony, in fact, executed my 10-times great-grandmother, Mary Dyer, in 1660 for being a Quaker—a story for another blog post. What actually surprised me about Edward’s situation is that he didn’t really get into too much trouble in Dover, despite being a heretic. He was even appointed to a surveying committee in 1654, a position of responsibility (Scales 1900). I was also surprised that he later moved to Nantucket, which is closer to Boston than Dover is.

Further research into religious intolerance in New England and the history of Nantucket clarified some things for me. First, while religious intolerance was part of all Puritan communities in New England, most did not take it as far as Massachusetts Bay did. Even Quakers, the most problematic sect from a Puritan perspective, were usually fined and banished from the various colonies, rather than whipped, mutilated, and/or hanged as they were in Massachusetts Bay (Miller 2008). This less rigorous approach to religious dissent seems to hold true in Dover. Prior to about 1660, court records show few prosecutions for dissent, with the exception of Edward Starbuck, who perhaps was made an example of because he was a church elder. After 1660, though, far more residents of Dover were fined or put in the stocks for missing church or consorting with Quakers, a fact a later minister attributes to a rise in Quaker sentiment during that time (Quint 1884).

More importantly, Nantucket had an unusual position in the history of New England. While it was initially part of the grant made to the Plymouth Company, it was largely ignored by the English colonists until 1659 when Thomas Mayhew, who had purchased the island from the Company, sold shares to a group of colonists, including Edward Starbuck. Of course, the island was already inhabited by the Wampanoag people and had been for thousands of years.

The colonists did pay some of the local sachems for deeds to the land, but as a later petition by tribal members noted, these men had no authority to sell the land to the colonists. The colonial court ruled the colonists’ deeds valid anyway. The Wampanoag people on Nantucket were decimated by disease, alcohol, and indebtedness over the next century but still played a significant role in the development of Nantucket as a center of the whaling industry, working on whaling crews but seeing little of the profit (Vickers 1983).

Starbuck, Alexander. 1924. “Nantucket House-Lot Section 1666-1680.” In The History of Nantucket. Boston, MA: C.E. Goodspeed & Co. Page 56.

In 1664, the English acquired New Amsterdam from the Dutch, and King Charles II granted the colony, together with Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard, to his brother, the Duke of York. This situation turned out to be beneficial for those founders of Nantucket who, like Edward Starbuck, had been persecuted for religious dissent. Nantucket was a long way from the colonial seat in New York City, and the leaders of what was now New York generally continued the policy of religious tolerance that had existed under the Dutch (O'Connor 1936). That religious tolerance extended to Nantucket, where Baptists, Presbyterians, and Quakers all flourished, with the Quaker group led by Mary Coffin Starbuck, wife of Edward’s only surviving son, Nathaniel. By the time Nantucket was returned to Massachusetts in 1692, the worst of the religious persecution was over. Nantucket’s religious diversity was allowed to continue, and by the mid-18th century, a substantial percentage of the island’s inhabitants were Quakers, and the island’s economy was dominated by whaling (Macy 1835; Starbuck 1924).

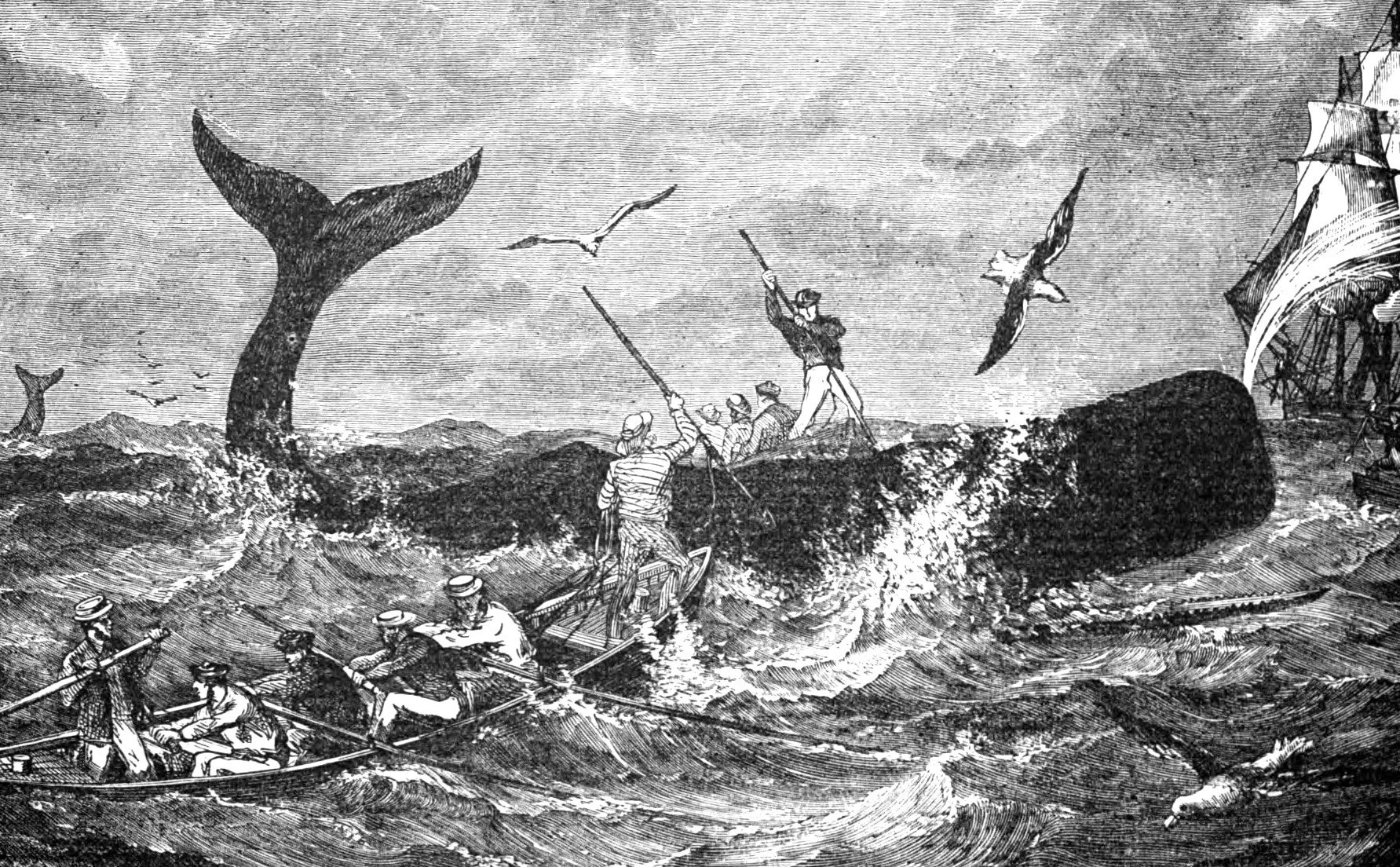

Macaulay, James. 1880. “Whale Fishing.” In All True, Records of Peril and Adventure by Sea and Land, Remarkable Escapes and Deliverances etc.: A Book of Sunday Reading for the Young. New York: A.D.F. Randolph & Co. Page 27.

For anyone who has read or seen a film version of Moby-Dick, the name Starbuck will have connections other than coffee. In the novel, Starbuck was the chief mate aboard Captain Ahab’s ship and was a Quaker from Nantucket. While fictional, this is highly plausible. The Starbuck family was a major player in Nantucket’s whaling industry (Starbuck 1924). Herman Melville, who served briefly on a Nantucket whaler as a young man, knew what a whaling ship and its crew were like and, along with the Quaker Starbuck, included a Wampanoag man and a Black man among Ahab’s crew. Enslaved Africans were brought to Nantucket by the end of the 17th century, and a community of freedmen developed over time on the island, providing considerable racial as well as religious diversity (Farr 1983).

So is there any connection between my ancestor and Starbucks Coffee Company? The founders of Starbucks have largely avoided crediting the name to Moby-Dick, but recent research by blogger Adam Mellion suggests that the novel is the most likely origin of the company’s name. He has also pointed out another Nantucket link to coffee. One early English settler of Nantucket was Peter Folger, who was an Baptist and worked as a surveyor, weaver, miller, and Wampanoag translator on the island. A descendant of Peter’s was partner in, and eventually owner of, what became the Folger Coffee Company (Mellion 2024). So the next time you think about coffee—be it Starbucks or Folgers—keep in mind the legacy of Nantucket and its heretical colonists.

[1] The records of the Court of Assistants for this era are fragmentary, at best, and I’ve not found any reference to Edward Starbuck in them (Cronin 1928).

Unknown artist. c1898. Between the Wharves, Nantucket, Mass. Detroit, MI: Detroit Publishing Company. Image from The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library.

Works Cited

Cronin, John F., ed. 1928. Records of the Court of Assistants of the Colony of the Massachusetts Bay, 1630-1692. Vol III. Boston, MA: County of Suffolk.

Farr, James. 1983. “A Slow Boat to Nowhere: The Multi-Racial Crews of the American Whaling Industry.” The Journal of Negro History 68 (2): 159-170.

Macy, Ored. 1835. The History of Nantucket. Boston, MA: Hilliard, Gray, and Co.

Mellion, Adam. January 14, 2024. “Call Me Starbucks.” All Visible Objects. Blog.

Miller, Robert T. 2008. “Religious Conscience in Colonial New England.” Journal of Church and State 50 (4): 661-76.

Quint, Alonzo H. 1884. “The Memorial Address.” In The First Parish in Dover, New Hampshire: Two Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary. Dover, NH: Printed for the Parish.

Scales, John. 1900. Historical Memoranda Concerning Persons and Places in Old Dover, N.H. Vol. 1. Dover, NH: Dover Enquirer Press.

Scales, John. 1923. History of Dover, New Hampshire. Vol. I. Dover, NH: Printed by authority of the City Councils.

Starbuck, Alexander. 1924. The History of Nantucket. Boston, MA: C.E. Goodspeed & Co.

Vickers, Daniel. 1983. “The First Whalemen of Nantucket.” The William and Mary Quarterly, 40 (4): 560-583